“Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon.” ~Milton Friedman

Inflation is at 7%, its highest level since 1982. The ability of Congress or the Biden Administration to curb inflation is limited, at best. Responsibility for addressing inflation will fall to the arm of the federal government primarily responsible for monetary policy, the Federal Reserve Board (the “Fed”).

As the U.S. approaches full employment, the Fed is turning its attention to reducing inflation by decreasing the amount of money available to purchase goods and services. The Fed will pursue this goal by targeting a higher federal funds rate, conducting related open market operations, and reversing quantitative easing – a relatively new tool in the monetary policy toolbox. What are the Fed’s goals and how does pulling on these somewhat mysterious levers help bring down inflation?

The result of these activities is expected to be several small interest rate increases over the course of 2022. Should you be concerned? The Fed has forecast that it will not be taking radical action, but rather returning to a combination of policies that are reassuringly consistent with those of the last 40 years.

Maximum Employment, Stable Prices

Congress passed the Federal Reserve Act in 1913, in the wake of the 1907 financial panic. Today, the Fed consists of a system of 12 regional Federal banks overseen by a Board of Governors. The Fed’s Open Market Committee (the “FOMC”) consists of this Board and five presidents of the regional banks, overseen by the Chair of the Board, Jerome Powell.

The Fed’s mission is to manage the financial system to promote optimal macroeconomic performance. Congress set two statutory goals for the Fed: maximum employment and stable prices.

Because labor markets are constantly changing, setting a numerical target for maximum employment is difficult. A practical test is: if one wants a job, is it available? Some economists use a 4% unemployment rate as an indicator of when the economy is at maximum or full employment. The unemployment rate was at 3.9% in December 2021, a sign that the Fed is currently meeting this goal.

When it comes to stabilizing prices, the Fed’s target is a 2% inflation rate. However, the inflation rate marched steadily upward during 2021, to the current 7% level.

Percent Change from Year Ago

Monthly Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers

While there are various complexities and factors at play (See What’s Up With Inflation? and Fact or Fiction? Investment Truths for 2022), the Fed’s Board is now in agreement that it must turn its attention to reducing the inflation rate in 2022.

Monetary Policy and the Federal Funds Rate

The Fed attempts to reduce the inflation rate by reducing the money available to purchase goods and service.

Businesses and consumers often borrow money for purchases. By reducing the supply of money, the Fed increases interest rates, making borrowing more expensive. If the cost of borrowing rises, demand for borrowed money goes down. Less borrowed money means less money for purchases in the economy. Reducing demand in this way is “contractionary” monetary policy. The reverse, or “expansionary” monetary policy, is designed to increase demand and economic growth.

Since 1995, the primary approach the Fed has taken toward contracting or expanding the supply of money is to target a specific federal funds rate. The “federal funds rate” is confusingly named – the rate is not charged by the Fed but instead represents the interest rate that banks charge each other for short-term loans.

As this federal funds rate moves up and down, other interest rates – for car loans, mortgages and other forms of commercial and consumer credit – generally follow. As those rates move up and down, the amount businesses and consumers borrow to make purchases goes up and down – the higher the interest rate, the less borrowed. If the amount of money available to make purchases goes up, prices and inflation typically follow. Today, with inflation moving higher, the Fed is seeking to reduce the amount of borrowed money in the economy and therefore push prices and inflation down.

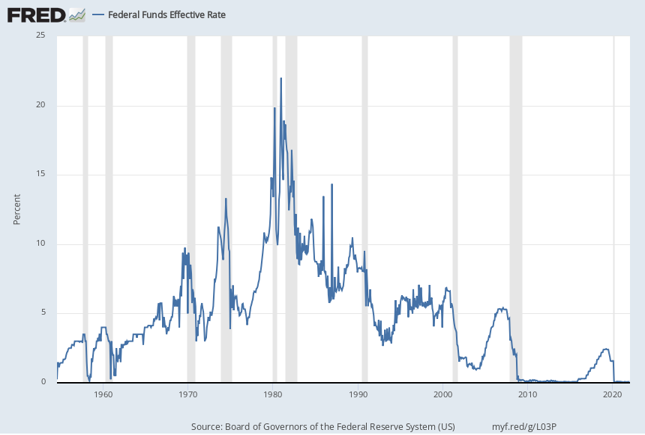

Moving the Federal Funds Rate

To drive the federal funds rate up or down, the Fed’s FOMC uses open market operations. Prior to 2008, these operations consisted primarily of buying or selling short-term U.S. Treasury bonds from or to banks. When the Fed buys these bonds, it is in effect creating money in the financial system. A greater supply of money moves the price of money – interest rates – down, and so drives the federal funds rate lower. When the Fed sells bonds, it takes money out of the system, driving the rate higher. Historically, to achieve its 2% inflation target the Fed has moved its targeted federal funds rate within a wide range, roughly 0% to 20%.

Effective Federal Funds Rate

1955-Present

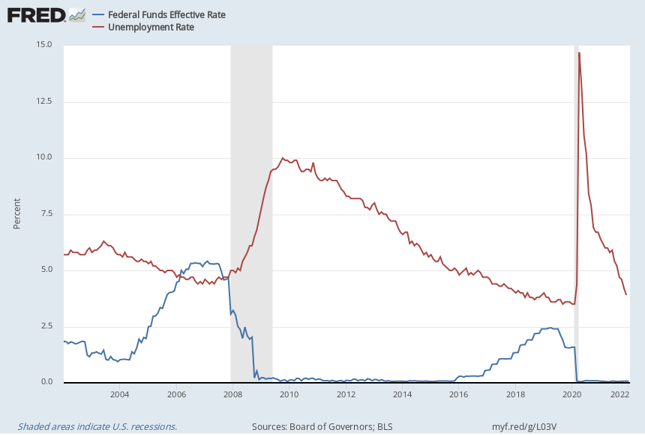

The Fed responded to both the Great Recession and the COVID-19 pandemic recession with an expansionary monetary policy to increase employment, one of its two main goals. However, after the Great Recession and the onset of the pandemic, the effective federal funds rate was at or near zero – yet the unemployment rate remained high.

Effective Federal Funds Rate

Unemployment Rate

2002-Present

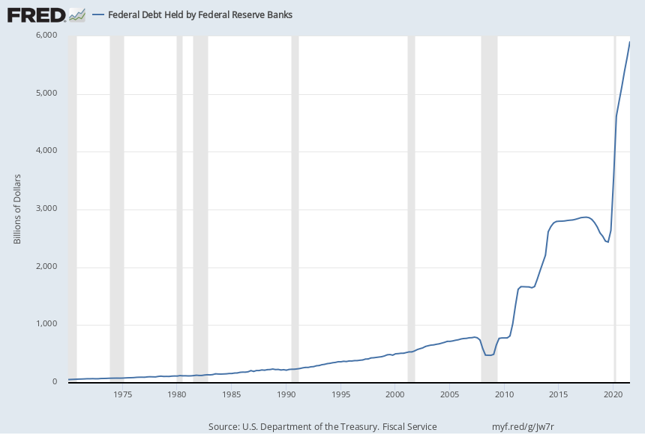

Since 2008 the Fed has used an asset-buying stimulus program known as “quantitative easing” in order to pump even more money into the economy. In addition to the relatively modest amounts of short-term U.S. Treasury bonds, the Fed has also bought long-term U.S. Treasury bonds and mortgage-backed securities, which currently total $8.5 trillion on the Fed’s books. The dramatic increase in Fed holdings of Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities is illustrated below.

Federal Debt (U.S. Treasuries)

Held by Federal Reserve Banks

Mortgage-Backed Securities

Held Outright by the Fed

A Return to “Normal”

To address today’s inflation, the Fed expects to increase its federal funds rate target several times over the course of 2022. These changes are typically small, one-quarter percentage point (0.25%) increases, which allow the financial markets and businesses to anticipate and adjust smoothly to the rate hikes.

Over time, these increases will raise the federal funds rate back to a higher level that, historically speaking, is more typical. One benefit of going back to that higher level is that the Fed will be able to pursue its goals in the future by adjusting the federal funds rate back down, without resorting to the more aggressive, quantitative easing practice of multi-billion dollar securities purchases.

As part of this effort, the Fed expects to start selling the assets it has purchased since the Great Recession, in effect reversing “quantitative easing.” While the exact timing and pace are to be determined, this action would reduce the size of the Fed’s balance sheet and, like the anticipated move up in the federal funds rate, be a return to a more historically “normal” scenario.

These actions, if taken too quickly or too aggressively, could hinder economic growth. The Fed now believes that addressing the threat of persistent, high inflation is more important. The Fed can always revise or even reverse its approach if the economic data shifts in unexpected ways.

A Reassuring Shift

Change can be disconcerting. This is particularly so when the change is an area that is complex and technical like the operations of the Federal Reserve. Understanding the terminology and reasons for those operations can be helpful.

The Fed is in many ways returning to its more traditional approach to monetary policy, which is a sign that, after nearly two years of pandemic-related disruption, the overall economy is moving toward a more conventional environment.