This article was written before stock indices moved into a bear market rather than a correction.

However, the same principles presented continue to apply.

“In investing, what is comfortable is rarely profitable.”

– Robert Arnott

The market declines this year are painful. However, these types of declines are surprisingly

frequent. Understanding how to respond to market corrections is critical. Behavioral economics

teaches that our psychology can lead to common, irrational mistakes in these down markets.

Well-informed investors anticipate and avoid these mistakes through a sound, disciplined

financial approach.

Markets Have “Corrected” Across the Board

2022 has been marked by corrections in stock, bond and other investment markets. A market

“correction” is a decline of more than 10% from its most recent peak. A “bear” market is a

decline of more than 20%.

Stock Market Correction

S&P 500 and Dow Jones Industrial Average: 2022 YTD

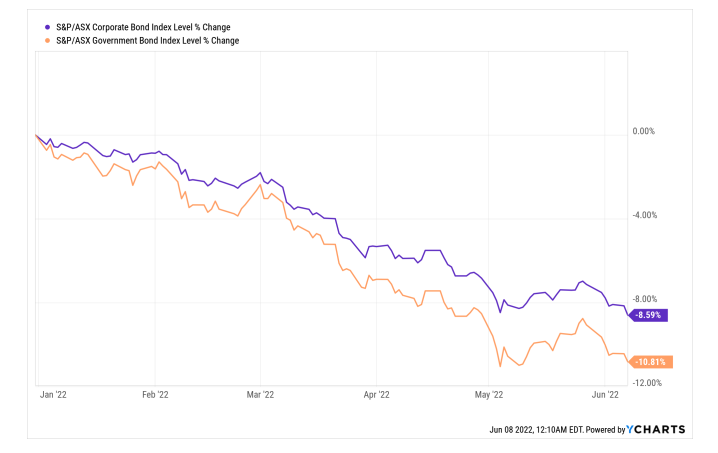

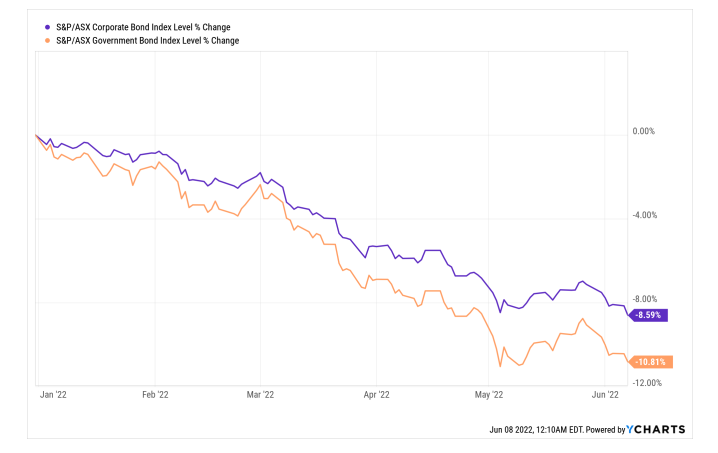

In addition to the stock market, investors have also faced a correction in the government bond

markets, and near-correction in the corporate bond market.

Bond Market Declines

Corporate and Government Bond Indices: 2022 YTD

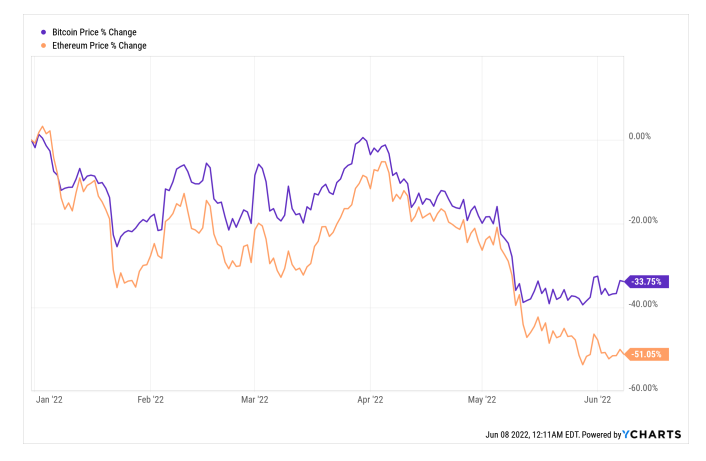

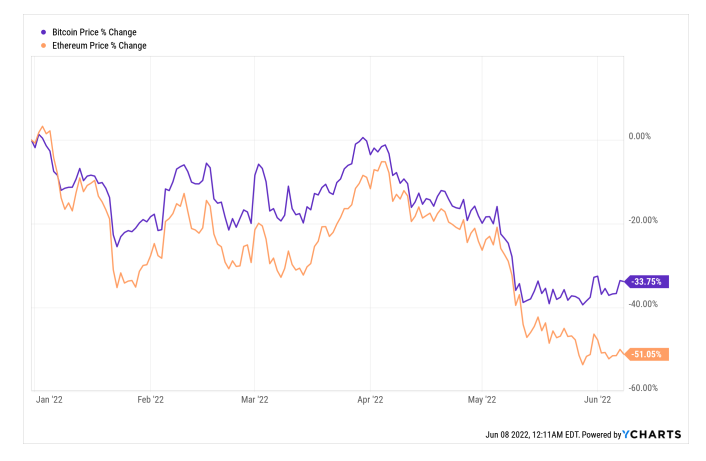

Investors who may have ventured into the “Wild, Wild West” of cryptocurrencies have faced

even more severe declines. There one finds a severe “bear” market, even for the supposedly

“safer” cryptocurrencies, Ethereum and Bitcoin.

Cryptocurrency Bear Markets

Bitcoin and Ethereum: 2022 YTD

Markets “Correct” More Often Than You May Think

Market corrections are common, on average occurring every year or two. The view of

current investors may be overly optimistic due to the recent “bull” market. According to

Kiplinger, this rising market continued from March 2009 to March 2020, for about 11

years – the longest bull market in U.S. history. However, a Yardeni Research analysis shows

that between 1980 and 2020, there were 18 “corrections” within the S&P 500 – on average,

once every two years or less. A wise investor will have a thoughtful approach to understanding the emotional response to periodic drops in both overall market values and

specific stock prices.

Markets May Be Rational, Individual Investors Not So Much

A cornerstone of traditional finance training is the Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH).

EMH holds that share prices reflect all information, and that as a result investors cannot

outperform the overall market. EMH is based in part on the belief that investors act

rationally, using available information to make objective decisions about the appropriate

price for a security based on its prospects to generate future cash flows.

Although the overall market may, over the long run, behave in accordance with EMH,

many modern economists believe that individual decision-making is not consistently

rational. In fact, those decisions are often driven by a common psychological phenomenon sometimes known as “loss aversion.”

Loss aversion may sometimes lead to investment decisions that are too conservative.

For example, selling the stock of a growing company early, prioritizing low-return investments like certificates of deposits, or holding cash rather than investing in stocks. These

behaviors can lead investors to miss significant returns in rising markets. We addressed

how to manage these behaviors in an article last fall. (See Pain vs. Gain: Taming Your

Emotions in Uncertain Markets.)

Risky Behavior in Down Markets: Holding On Too Long

Loss aversion can also lead to behaviors that actually increase investment risk. Though the

result is different, the cause is the same – individuals seek to avoid losses, even when doing

so does not make sense in strictly “rational” economic terms. In addition, most people

want to avoid feelings of regret. The potential for regret can arise when an investor’s view

of the value of a stock is “anchored” to the original purchase price, but the current price

is lower.

For example, say you buy a stock based on a strong belief in the products of the underlying

business, at $100 per share. The business subsequently underperforms and the stock price

drops 80%, to $20 per share. There is little evidence that the business will start to perform

at a level that would justify a return to the $100 share price. The company is not bankrupt,

though, and there’s a chance it will recover. Objectively, the investor is better off selling

the stock, taking the capital loss (and the possible tax benefit), and putting the $20 into an

investment with better prospects.

However, selling the stock means realizing the $80 loss. It also means the possibility of

regret if the stock does, miraculously, return to the $100 price level. As a result, investors

may hang onto the stock too long to avoid these negative emotions – feelings of loss

and regret.

Risky Behavior in Down Markets: Selling to Time the Market

Another, perhaps more common mistake in falling markets is to sell to avoid further losses.

Selling the stock of a failing business is sensible. Selling most or all of your stocks, and sitting

on the cash, runs the risk of missing out on the gains when the market eventually rallies.

Since 2009, there have been at least two instances in which the S&P 500 rose by roughly 30%

in less than two months. (See, again, Pain vs. Gain: Taming Your Emotions in Uncertain

Markets.) If you are holding cash rather than stocks, you miss these returns, which are

critical to overall financial results.

This potential error may be driven by the combination of the desire to avoid losses and

a misplaced confidence in the ability to time the market. A common error by some

investors is to “trust their gut” with respect to timing and other market dynamics.

However, these types of intuitive insights are unreliable in generating returns. As an

example, consider an investor who chose to sell most of their stock holdings during the

Great Recession of 2008, or after the pandemic emerged in 2019. How likely is it that the

same investor would have decided to plow all that cash back into stocks in March 2009, or

March 2020, just when both of those recent periods of 30% gain were set to begin?

Know to Protect Thyself

One way to make better financial decisions for yourself is to understand the emotional

tendencies of all investors. Understanding that an “irrational” desire to avoid losses can

cause you to hold onto a stock too long, or sell out of a market too soon, can help you

avoid making those mistakes. Likewise, understanding the risks of staying out of the

market based on a belief in an ability to time purchases can help you take advantage of

periods of extraordinary returns. Consulting with a trusted financial advisor is also an

excellent way to discipline your emotions, and make objectively sound portfolio decisions.

Cindy Alvarez is a Senior Wealth Management Advisor and an Owner of Wambolt & Associates.

Bob Newkirk is a registered C.P.A, former investment banker, and prior Fellow in Law and Economics

at the University of Chicago. The information in this article is for general informational purposes,

and is not individual financial advice.