“The arithmetic makes it plain that inflation is a far more devastating tax than anything that has been enacted by our legislatures. The inflation tax has a fantastic ability to simply consume capital.” ~Warren Buffet

How does inflation “consume” an investor’s capital and act as a type of “tax”? As inflation increases, the actual value an investor would expect to receive from an investment in the future decreases, which drives the current price of the investment down. To understand better why this happens, we need to understand how bonds and stocks are priced, and how inflation directly affects those prices.

Inflation?

Inflation is the increase in the price level of goods and services in an economy over time. With inflation, the value of a currency, like the U.S. dollar, decreases. If you have dollars under your mattress, they become less and less valuable as inflation increases. This is because the amount of purchasing power of each dollar decreases as inflation increases.

Investors have taken notice of inflation over the years, particularly in May, when the inflation rate measured by changes in consumer prices hit an annual rate of 5%. Officials from the Federal Reserve bank stated that this increase should be temporary, or “transitory.” However, since this was the biggest jump in inflation since 2008, many investors have become concerned. (See What’s Up With Inflation?)

Asset Prices & the “Time Value of Money”

Prices for financial assets like bonds and stocks in the long run are based on the value today of the cash flows an investor expects to receive in the future. In general:

You will pay more today for an asset that pays you more in the future. You will pay less for an asset that pays you less.

But, exactly how much should you pay today for those future cash flows? You would consider many factors, including the riskiness of the business, but here we will focus on the time value of money.

The time value of money is the commonsense notion that you would rather have money today than tomorrow. Why? So, you have access to the funds for other purposes, including making other investments. Putting risk aside for a moment, the time value of money means that you would insist on paying less than $10,000 today, in exchange for $10,000 five years from now.

Real and Nominal Return on Investment

How much less? That is where inflation comes into play. Inflation affects the time value of money because of the difference between “nominal” and “real” returns. Nominal figures are basically stated prices or interest rates, those you read online or in the paper. For example, the average 30-year fixed mortgage rate was 2.98% as of July 1, 2021.[1]

Real returns take into account inflation. You subtract the expected inflation rate from the nominal figure to get the real figure. This is the “real” return, i.e., the benefit you receive after adjusting the return for the effect of rising prices. If the stated or nominal rate is 10%, but expected inflation is 8%, your real rate of return will be 2%. The 2% represents how much additional purchasing power you will actually gain.

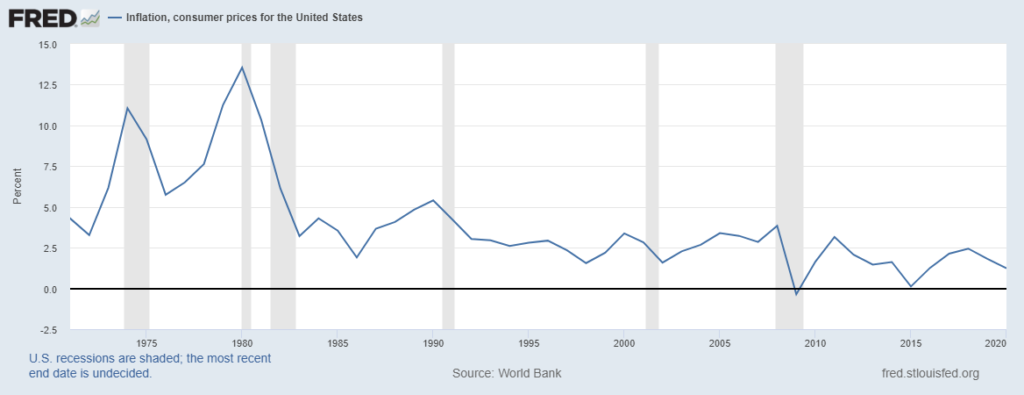

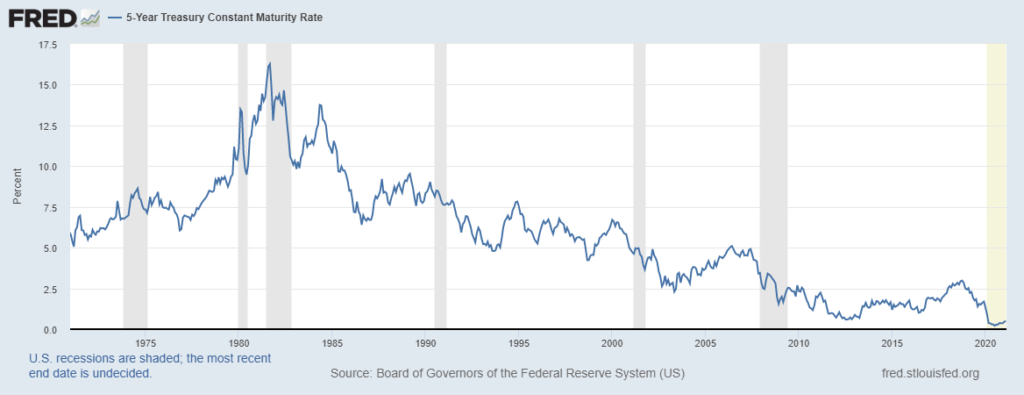

Because inflation drives nominal interest rates up, it drives prices for investments down. U.S. Treasury bonds are generally considered a good source for “risk-free”, nominal rates of return. There are two graphs below. The first shows consumer price inflation since 1970; the second the nominal rate of return on a 5-year Treasury bond for the same period.[2]

The two graphs have similar shapes because as inflation goes up, the nominal rate on the bond goes up. In 1980 the nominal rate of return on the 5-year Treasury was over 10%, much higher than today, but the annual inflation rate was 13.5%. As a result, the real rate of return on the 5-year bond was much lower than the nominal return in 1980, and not dramatically different than the real rate of return today.

As inflation goes up and down…

… so do the rates of return on bonds.

Inflation Effects on Bond and Stock Prices

Rising inflation rates generally drive higher nominal “risk free” rates of return, which in turn drives lower prices for stocks and issued bonds. Let’s return to the example of an investment that promises you $10,000 in five years. Based on today’s 5-year Treasury rate of 0.89%, with respect to the time value of money only, you would pay about $9,570 today for the investment.

Forty years ago, in June 1981, the nominal rate on a 5-year Treasury bond was 14.25%. Using that rate, you’d pay only about $5,140. Why the big difference in the rates? Because inflation in 1981 was over 10.3%, compared to 1.2% in 2020. In this illustration, the higher inflation rate drove down the price of the investment by about 46%.

Although bonds and stocks are more sophisticated investments than the hypothetical presented here, the principles remain the same. A bond pays you in the future in the form of periodic interest, usually in a fixed amount, and then a lump sum at its maturity. A stock pays you in the future, in the form of periodic dividends, or you may be able to sell it at a higher price.

In either case, the investment generates future cash flows. As the hypothetical illustrates, if investors expect inflation to increase, the nominal risk-free return rate increases, and the amount an investor will pay for those cash flows will go down. Therefore, market prices will also usually decline.

Conclusion

If government policies drive expectations for inflation up, investors can expect a negative effect on the prices of existing bonds and stocks. The size of the inflation effect on market prices is based on any number of factors, including the life of the bond, the pricing power and projected future growth of a business, and how long the higher inflation is expected to last. Due to this complexity, if you are concerned about how inflation might affect your portfolio, it’s important to consider a thoughtful and thorough approach to possible adjustments with your investment advisor.

Authored by Cindy Alvarez & Bob Newkirk

Cindy Alvarez – Senior Wealth Management Advisor with Wambolt & Associates.

Bob Newkirk is a registered C.P.A, former investment banker, and prior Fellow in Law and Economics at the University of Chicago.